|

Contents

section III-b: politics

'Be the master and maker of

yourself'

F.

Nietzsche

Ordering, democracy

and utopia

In section

III-a the practice of the personal was

discussed in the sense of meaning and

ritual. The idea was that wishing

respect for oneself, the other also

needs to be respected - nothing but a

fair deal. The religion of regularly

associating for the sake of a holy

person then, who, including a holy

scripture, really is worthy the full

respect, constitutes a school of

learning. In history the schools are

there in succession. From the

consecution of the schools one can

derive in what way they, each for

themselves, fell short and in what

respect the science of the person was

in need of an upgrade, of an

adaptation to time and circumstance.

To this upgrading there is never an

end, one unrelenting has to keep to

time; the dynamical nature reflected

in the culture, commands a constant

reorienting and readapting, which, as

we saw with the method, onlyprogressing non-repressively

truly entails the progress. Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677)

in his Theological-political

Treatise said that God's

providence is to be understood as the

order of nature itself and

also

Vyāsa described it in the Bhāgavatam likewise,

calling nature the virāth rūpa

or the gigantic form of God. To the

need of the constant adaptation to

that personally understood God, the

dynamical element of the time of

living nature, as being the universal

object of worship, is recognized.

The idea of God as being a dynamical

natural reality at the disposition of

a personal choice, is also, in the

sense of an alternative paradigm,

mentioned by modern physicists like David Bohm (1917-1992)

in Wholeness and the Implicate

Order and Fritjof

Capra (1939), in e.g. his book The

Turning Point (1982). So

even though we may be erring with the

constancy of lightspeed, new physics offers a

helping hand, especially those

contributions that do not deny the

possibility of the existence of a

connecting element like the ether. And this is

politically of importance, because the

ideation of natural science happens to

form the basis for the rest of the

sciences, just like the story of

creation constitutes the basis for the

Bible and the Purāna (an Indian book

of holy stories). The idea of how the

world originated and functions is

indicative for the rest of the

cultural superstructure. Reasoning

from quantum-mechanics and pushing off

against a mechanical, fixed, singly

cartesian dimensionality outside the

dimension of the spacetime of the new

physics, Capra almost like the new-age

guru Osho most poetically arrives at

sayings like: 'There is motion but

there are, ultimately, no moving

objects; there is activity but there

are no actors; there are no dancers,

there is only the dance.' Also

new-age authors like Marilyn

Ferguson at length

dilate on the consequences of the

dynamical indeterminacy of the true

energetic self of the universe, in

which we, to her opinion, with that

premise being of selfrealization, are

all connected in what she (in 1982)

calls the 'aquarian conspiracy'.

Concerning the resistance against it

she states: 'It's not so much that

we're afraid of change or so in love

with the old ways, but it's that

place in between that we fear . . .

. It's like being between trapezes.

It's Linus when his blanket is in

the dryer. There's nothing to hold

on to.' The old shoes are

worn, but the new ones are not yet

comfortable, but it is another type of

consciousness, another way of seeing,

which we materially political,

technical and legal, or else

individually therapeutic, have to give

shape to following the principle, in

order to make the transition with the

order of time possible. Ferguson is

right in her option of connectedness

in this, of the basically operating

from the inside, with a 'trojan heart'

taking up the karma, as she put it in

an

interview in 1995; the same

old science time and again has to be

reformulated and adapted in faith with

the dynamical and personal nature, the

way we also, time and again, have a

new constellation of the same old

planets. Without that revaluing,

without that adaptation to place,

culture, person and time, one is fixed

and one fallen thereof has lost

one's way or is bewildered in

attachment, as Vyāsa puts it (S.B. 4.8: 54). And this is

politically of importance, because the

ideation of natural science happens to

form the basis for the rest of the

sciences, just like the story of

creation constitutes the basis for the

Bible and the Purāna (an Indian book

of holy stories). The idea of how the

world originated and functions is

indicative for the rest of the

cultural superstructure. Reasoning

from quantum-mechanics and pushing off

against a mechanical, fixed, singly

cartesian dimensionality outside the

dimension of the spacetime of the new

physics, Capra almost like the new-age

guru Osho most poetically arrives at

sayings like: 'There is motion but

there are, ultimately, no moving

objects; there is activity but there

are no actors; there are no dancers,

there is only the dance.' Also

new-age authors like Marilyn

Ferguson at length

dilate on the consequences of the

dynamical indeterminacy of the true

energetic self of the universe, in

which we, to her opinion, with that

premise being of selfrealization, are

all connected in what she (in 1982)

calls the 'aquarian conspiracy'.

Concerning the resistance against it

she states: 'It's not so much that

we're afraid of change or so in love

with the old ways, but it's that

place in between that we fear . . .

. It's like being between trapezes.

It's Linus when his blanket is in

the dryer. There's nothing to hold

on to.' The old shoes are

worn, but the new ones are not yet

comfortable, but it is another type of

consciousness, another way of seeing,

which we materially political,

technical and legal, or else

individually therapeutic, have to give

shape to following the principle, in

order to make the transition with the

order of time possible. Ferguson is

right in her option of connectedness

in this, of the basically operating

from the inside, with a 'trojan heart'

taking up the karma, as she put it in

an

interview in 1995; the same

old science time and again has to be

reformulated and adapted in faith with

the dynamical and personal nature, the

way we also, time and again, have a

new constellation of the same old

planets. Without that revaluing,

without that adaptation to place,

culture, person and time, one is fixed

and one fallen thereof has lost

one's way or is bewildered in

attachment, as Vyāsa puts it (S.B. 4.8: 54). It is,

varying to the classical themes of

wisdom, always an unfinished

structure. Historically we thus first

had the Vedic culture itself that, in

her rule defeated by the time, came to

a fall on the basis of the familial

attachments of the aristocracy, which,

having become a burden to mother

earth, had to wipe itself off the

planet at the battlefield of the great

war of the Mahābhārata. Greek

philosophy the same way, with the

philosopher Socrates being condemned

to drink the cup of poison, came to

a fall delivering the proof that

undermined the authority of the state

of the lesser wisdom of the

pretentious formalism of the ruling

class; with the morale drawn stated in

the Gītā (in 3: 39): 'one must not upset

the people

with ones wisdom'. Buddhism

came, with the foodpoisoning leading

to the death of the Buddha, to a fall

in the human tolerance for both

impurities and the negation of the

world as being an illusion; like an

Arjuna blowing the conchshell, one has

to hold one's ground. Judaism came to

a fall by it's impersonal,

institutional denial of the living

personal God, the nevertheless as

inevitable recognized Messiah or avatāra.

Christianity falls down from a poor

concept of time with an insufficiently

expressed Lord Jesus who in this could

not be more specific than stating that

it, with the then (45 v. Chr., 709

A.U.C) abolishing of the lunar

calendar since Julius Caesar, on earth

indeed had to happen as in heaven; for

the Lord, the Father happens to be

kāla, the Time. Islam, which

with the order of time for God and His

ether, with the times of prayer did

obey the sun - recognized as the will

of God, Allah - following, comes to a

fall by her fundamentalistic,

jihadistic lust for lording over, and

being of disrespect for, other forms

of belief; for he who always wants to

win will, by the golden rule, have to

loose it sooner or later as a

consequence. There irrevocably happen

to be different avatāras and

ditto devotional cultures that each

have their own historical purpose It is,

varying to the classical themes of

wisdom, always an unfinished

structure. Historically we thus first

had the Vedic culture itself that, in

her rule defeated by the time, came to

a fall on the basis of the familial

attachments of the aristocracy, which,

having become a burden to mother

earth, had to wipe itself off the

planet at the battlefield of the great

war of the Mahābhārata. Greek

philosophy the same way, with the

philosopher Socrates being condemned

to drink the cup of poison, came to

a fall delivering the proof that

undermined the authority of the state

of the lesser wisdom of the

pretentious formalism of the ruling

class; with the morale drawn stated in

the Gītā (in 3: 39): 'one must not upset

the people

with ones wisdom'. Buddhism

came, with the foodpoisoning leading

to the death of the Buddha, to a fall

in the human tolerance for both

impurities and the negation of the

world as being an illusion; like an

Arjuna blowing the conchshell, one has

to hold one's ground. Judaism came to

a fall by it's impersonal,

institutional denial of the living

personal God, the nevertheless as

inevitable recognized Messiah or avatāra.

Christianity falls down from a poor

concept of time with an insufficiently

expressed Lord Jesus who in this could

not be more specific than stating that

it, with the then (45 v. Chr., 709

A.U.C) abolishing of the lunar

calendar since Julius Caesar, on earth

indeed had to happen as in heaven; for

the Lord, the Father happens to be

kāla, the Time. Islam, which

with the order of time for God and His

ether, with the times of prayer did

obey the sun - recognized as the will

of God, Allah - following, comes to a

fall by her fundamentalistic,

jihadistic lust for lording over, and

being of disrespect for, other forms

of belief; for he who always wants to

win will, by the golden rule, have to

loose it sooner or later as a

consequence. There irrevocably happen

to be different avatāras and

ditto devotional cultures that each

have their own historical purpose  and

maintenance. Reformation, to the

self-willed of the compassion and the

integration of the social science,

must with the Christian fall-down in

theological opposition and

one-sidedness, next expand into a more

multicultural, rationalistic-empirical

enlightenment of expanding

consciousness, for the reformer S'rī Caitanya (1486-1543)

happened to conclude to an

'inscrutable oneness in diversity'.

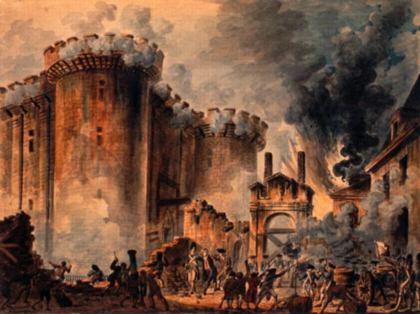

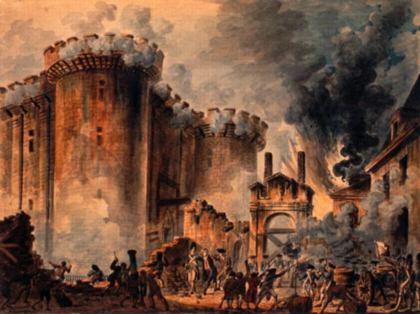

The culture of Enlightenment next,

entirely predictable from natural

entropy*, comes to a

fall because of a lack of consistency

and philosophical unequivocalness,

with the French Revolution finding

fault with all the elitary and false

subjectivistic/empirical

individualism; for as we knew already:

the

philosopher must sing. Democracy

finally, in a social/revolutionary

sense defended with the French

Revolution, comes,

liberal/conservative finding itself in

opposition, to a fall in the degrading

of the dictatorships of communism,

militaristic fascism and

fundamentalism, for the cards of human

identity have been shuffled - as is

also Vedically confirmed. We

therewith, at the onset of the

twenty-first century, are awaiting

the definitive falldown of the, so

divinely lusty, but in particular

internationally most unjust,

capitalist dictate, with it's

sanctification of commercial strife,

with which then the limit will have

been reached of the possible forms of

corruption in the human

fields of action of the

nepotistic, viz. on friends and family

founded, democracy that constantly

runs into dictatorship, as was

discussed in section Ib. The Hindu

goddess of money, S'rī Lakshmī, in the

end is but a maid-servant of Lord

Vishnu, the Lord of goodness and

maintenance. The politics of friends,

the faulty combination of riches and

connectedness, and the democracy, do

not combine that well, so was shown

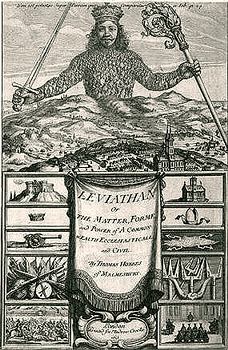

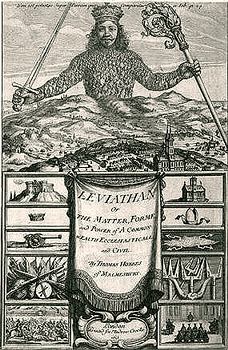

already by the philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679)

in his Leviathan. He only knew

three forms of state: the monarchy,

the democracy and the aristocracy,

viz. the people represented by one

man, by an assembly of all the ones

willing thereto and the representation

of a part of that gathering. Nepotism

makes democracy an aristocracy in

disguise, an aristocracy which Hobbes,

in case of dissension with the populace -

not so surprising with chosen 'nobles'

aiming at a more lucrative position in

industrial circles - , calls an

oligarchy, a culture of regents far

removed from the people and for the

countering of which one, in The

Netherlands e.g. notably, introduced

the monarchy. A monarchy which, with

many an illusory smoke curtain of

fake-democratic left-right changes,

proves itself to be a culture of

regents for which the populace has no

feeling but only dissent, is according

to Hobbes' logic then factually a

tiranny. In our case thus a capitalist

dictatorship: the confluence of a

faulty combination of capital and

philosophy on the one hand, with a

wrong notion of political power on the

other hand. It is only the complacency

of the consensus of the anxious,

capital-motivated majority,

repressing and violating minorities,

that thinks less of the volunteer in

service of God, calling him unemployed

by declaring him subservient to the

Mammon. And that being of an unjust

treatment neglects the rest of the

world; it makes one think one is a

democrat. False and ignorant

contentment with factual injustice

makes no stable state. And thus one

could say that the idea of the

majority of the voters, yet bears no

justice, and carries a false idea of

democracy. The republican democracy,

or else the monarchy, is only real in

case of justice, when everyone is done

justice and not just a 60% or 80%

majority. Thus we are faced with the

need of a general consensus about the

installation of election groups (see

also synopsis) in a

beforehand settled order not allowing

mutual repression with a

majority-vote: the majority must, on a

basis of consensus about this

self-knowledge, paradoxically manage

to protect itself against itself.

Rousseau (see also Charter of

Order) said about this in 'The

societal contract' II.3: 'In

order to really obtain the general

will, it is thus of importance that

there is no group split off in the

state and that each citizen only is

opinionated from his own stance.

Such was the case with the eminent

order of state of the great

Lycurgus. And if there would be any

groups split off, one must increase

their

number and see to it that they are

equally large as did Solon, Numa and

Servius. These measures of

precaution are the only right ones

to further that the general will (as

opposed to the specific will) for

sure shall clearly and constantly

surface and the people will not be

mislead.' The power is, divided

in a proportionate representation of,

classically tailored, fixed election

groups, thus to no one but to God (see

further 'A Small

Philosophy of Association'). and

maintenance. Reformation, to the

self-willed of the compassion and the

integration of the social science,

must with the Christian fall-down in

theological opposition and

one-sidedness, next expand into a more

multicultural, rationalistic-empirical

enlightenment of expanding

consciousness, for the reformer S'rī Caitanya (1486-1543)

happened to conclude to an

'inscrutable oneness in diversity'.

The culture of Enlightenment next,

entirely predictable from natural

entropy*, comes to a

fall because of a lack of consistency

and philosophical unequivocalness,

with the French Revolution finding

fault with all the elitary and false

subjectivistic/empirical

individualism; for as we knew already:

the

philosopher must sing. Democracy

finally, in a social/revolutionary

sense defended with the French

Revolution, comes,

liberal/conservative finding itself in

opposition, to a fall in the degrading

of the dictatorships of communism,

militaristic fascism and

fundamentalism, for the cards of human

identity have been shuffled - as is

also Vedically confirmed. We

therewith, at the onset of the

twenty-first century, are awaiting

the definitive falldown of the, so

divinely lusty, but in particular

internationally most unjust,

capitalist dictate, with it's

sanctification of commercial strife,

with which then the limit will have

been reached of the possible forms of

corruption in the human

fields of action of the

nepotistic, viz. on friends and family

founded, democracy that constantly

runs into dictatorship, as was

discussed in section Ib. The Hindu

goddess of money, S'rī Lakshmī, in the

end is but a maid-servant of Lord

Vishnu, the Lord of goodness and

maintenance. The politics of friends,

the faulty combination of riches and

connectedness, and the democracy, do

not combine that well, so was shown

already by the philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679)

in his Leviathan. He only knew

three forms of state: the monarchy,

the democracy and the aristocracy,

viz. the people represented by one

man, by an assembly of all the ones

willing thereto and the representation

of a part of that gathering. Nepotism

makes democracy an aristocracy in

disguise, an aristocracy which Hobbes,

in case of dissension with the populace -

not so surprising with chosen 'nobles'

aiming at a more lucrative position in

industrial circles - , calls an

oligarchy, a culture of regents far

removed from the people and for the

countering of which one, in The

Netherlands e.g. notably, introduced

the monarchy. A monarchy which, with

many an illusory smoke curtain of

fake-democratic left-right changes,

proves itself to be a culture of

regents for which the populace has no

feeling but only dissent, is according

to Hobbes' logic then factually a

tiranny. In our case thus a capitalist

dictatorship: the confluence of a

faulty combination of capital and

philosophy on the one hand, with a

wrong notion of political power on the

other hand. It is only the complacency

of the consensus of the anxious,

capital-motivated majority,

repressing and violating minorities,

that thinks less of the volunteer in

service of God, calling him unemployed

by declaring him subservient to the

Mammon. And that being of an unjust

treatment neglects the rest of the

world; it makes one think one is a

democrat. False and ignorant

contentment with factual injustice

makes no stable state. And thus one

could say that the idea of the

majority of the voters, yet bears no

justice, and carries a false idea of

democracy. The republican democracy,

or else the monarchy, is only real in

case of justice, when everyone is done

justice and not just a 60% or 80%

majority. Thus we are faced with the

need of a general consensus about the

installation of election groups (see

also synopsis) in a

beforehand settled order not allowing

mutual repression with a

majority-vote: the majority must, on a

basis of consensus about this

self-knowledge, paradoxically manage

to protect itself against itself.

Rousseau (see also Charter of

Order) said about this in 'The

societal contract' II.3: 'In

order to really obtain the general

will, it is thus of importance that

there is no group split off in the

state and that each citizen only is

opinionated from his own stance.

Such was the case with the eminent

order of state of the great

Lycurgus. And if there would be any

groups split off, one must increase

their

number and see to it that they are

equally large as did Solon, Numa and

Servius. These measures of

precaution are the only right ones

to further that the general will (as

opposed to the specific will) for

sure shall clearly and constantly

surface and the people will not be

mislead.' The power is, divided

in a proportionate representation of,

classically tailored, fixed election

groups, thus to no one but to God (see

further 'A Small

Philosophy of Association').

It is the

'easygoing' fake-democracy of

nepotism which is wasting her

qualities, because

of a lack of a societal structure, a

structure of fixed election groups

representative for all the

vocational and professional groups

(that thus balance each other at the

level of the government). And that

way it in fact thus discourages

those qualities. Therefrom one sees

the political character declining.

It is thus paramount to  educate

democracy anew,

or, as Alexis de

Tocqueville

(1805-1859) it right away in the

preface to his study on the democracy

in America stated: 'The

first duty, which is at this time

imposed upon those who direct our

affairs, is to educate the

democracy; to warm its faith, if

that be possible; to purify its

morals; to direct its energies; to

substitute a knowledge of business

for its inexperience, and an

acquaintance with its true

interests for its blind

propensities; to adapt its

government to time and

place, and to modify

it in compliance with the

occurrences and the actors of the

age. A new science of politics is

indispensable to a new world.

' In this context we stress the

notion of time and place, since in

this is found the essence of our

plea for the ether and the order of

time associated with it. This

re-education is, according Plato's 'The Republic' and his 'Seventh

Letter', the

responsibility of the philosopher

who then in fact is the boss, the

philosopher-king, or else the duty

of the king or ruler who then has to

be the philosopher. In the culture

of Vaishnavism around the works of

Vyāsa, one therefore speaks of the

spiritual master, or the ācārya,

who is the Mahārāja or the 'great

king', even though he stands more

for the liberation in devotional

service than for the enlightenment

of a sovereign power of

self-realization, which is more

reserved for the independent

esoteric guru. In the culture of

Christianity, which as yet was not

as conscious of the different types

of teachers as is explained section

III-a of the synopsis, this

would account for the difference

between the theologian preaching

liberation in being of service in

the religious community and the

psychologist/psychotherapist who

wants to educate the people in the

enlightenment of a philosophically

responsible way of self-realization

less of stressing outside

authorities. With the guidance

poised in between these two fires of

progress, it is clear that, without

the philosophically founded reform

or re-education of democracy,

without the constant upgrading of

what is supposed to be the

democratic order, and without the filognosy

thereto of the - by mediation of the

gnosis centering around the order of

time, thus mutually as being

dependent declaring of the

enlightenment of science and the

liberation in service of the person

of God, we inevitably will fall back

again into the darkness of

dictatorship and the moralism which

constitute the shadow-side of a

freedom ignorantly understood. The

competition between teachers of

initiation and teachers of

instruction along the dimensions of

the impersonal, local and person

minded, must, with the filognosy

and the respect therewith for the

enlightenment of the teachers

operating from within, come to a

stop. In terms of our filognosy each

must know

his place. It is like the japanese

confucianist philosopher Ogyu

Sorai

(1666-1628) said it in his Rules

of Study-6: 'A noble man therefore

is 'not prejudiced' in matters of

right and wrong, good and bad. Bad

is when something is not fed and

does not find its deserved place.

Good is to feed and let something

realize its full potential, and

see to it that it finds its place'.

This last section III-b is directed

at shaping this desired

revaluation of democracy

to the grace of our filognosy. educate

democracy anew,

or, as Alexis de

Tocqueville

(1805-1859) it right away in the

preface to his study on the democracy

in America stated: 'The

first duty, which is at this time

imposed upon those who direct our

affairs, is to educate the

democracy; to warm its faith, if

that be possible; to purify its

morals; to direct its energies; to

substitute a knowledge of business

for its inexperience, and an

acquaintance with its true

interests for its blind

propensities; to adapt its

government to time and

place, and to modify

it in compliance with the

occurrences and the actors of the

age. A new science of politics is

indispensable to a new world.

' In this context we stress the

notion of time and place, since in

this is found the essence of our

plea for the ether and the order of

time associated with it. This

re-education is, according Plato's 'The Republic' and his 'Seventh

Letter', the

responsibility of the philosopher

who then in fact is the boss, the

philosopher-king, or else the duty

of the king or ruler who then has to

be the philosopher. In the culture

of Vaishnavism around the works of

Vyāsa, one therefore speaks of the

spiritual master, or the ācārya,

who is the Mahārāja or the 'great

king', even though he stands more

for the liberation in devotional

service than for the enlightenment

of a sovereign power of

self-realization, which is more

reserved for the independent

esoteric guru. In the culture of

Christianity, which as yet was not

as conscious of the different types

of teachers as is explained section

III-a of the synopsis, this

would account for the difference

between the theologian preaching

liberation in being of service in

the religious community and the

psychologist/psychotherapist who

wants to educate the people in the

enlightenment of a philosophically

responsible way of self-realization

less of stressing outside

authorities. With the guidance

poised in between these two fires of

progress, it is clear that, without

the philosophically founded reform

or re-education of democracy,

without the constant upgrading of

what is supposed to be the

democratic order, and without the filognosy

thereto of the - by mediation of the

gnosis centering around the order of

time, thus mutually as being

dependent declaring of the

enlightenment of science and the

liberation in service of the person

of God, we inevitably will fall back

again into the darkness of

dictatorship and the moralism which

constitute the shadow-side of a

freedom ignorantly understood. The

competition between teachers of

initiation and teachers of

instruction along the dimensions of

the impersonal, local and person

minded, must, with the filognosy

and the respect therewith for the

enlightenment of the teachers

operating from within, come to a

stop. In terms of our filognosy each

must know

his place. It is like the japanese

confucianist philosopher Ogyu

Sorai

(1666-1628) said it in his Rules

of Study-6: 'A noble man therefore

is 'not prejudiced' in matters of

right and wrong, good and bad. Bad

is when something is not fed and

does not find its deserved place.

Good is to feed and let something

realize its full potential, and

see to it that it finds its place'.

This last section III-b is directed

at shaping this desired

revaluation of democracy

to the grace of our filognosy.

In

postmodern time, now, with the

synergy exhausted, being depressed

under the regime of artificiality

and fragmentation, we know faith as

such only as, the way the

philosopher Jean-Franēois

Lyotard

(1924-1998) put it, a negative,

cynical realization of lost

modernistic ideals, in which society

fell apart, like it was meat in the

showcase of the butcher, and the

hope for an all-embracing solution has been given up.

One could describe the postmodern

situation as the lamentation of the

grand but, about the human,

religious and moral freedom,

somewhat too negativistic, power

minded, philosopher F.

Nietzsche

(1844-1900): it concerns an

intellectual depression which,

literally in his case, with a brain

feverish of venereal disease seeing

a whipped horse in the street, in

tears falls around it's neck. On the

basis of the philosophers, who as

mere thinkers are not acceptable

anymore today, and with the social

activists among them, like Vladimir

Lenin

(1870-1924) and the early, equally

anti-religious  Karl Marx

(1818-1883), postmodern man knows

but one belief and one

mantra: 'that's nonsense!'. In a

depression being disappointed about

the enduring abuse by the human

being,

Religion is

nothing but hypocritical nonsense.

But was it not

the ancient philosopher Epicurus who

(341-270 b. Chr.) in his 'Letter

to Menoeceus' already said

that 'Not the man who denies the

gods that are worshiped by the

masses, but the one who ascribes

to the gods what the mass believes

about them, is godless'? Marx

is not entirely without a form of

belief or a God. He also builds on a

connecting element: 'There is, in

every social formation, a branch

of production which determines the

position and importance of all

others; and the relations

obtaining in this branch

accordingly determine the

relations of all other branches,

as well. It is as though light of

a particular hue were cast upon

everything, tinging all other

colors and modifying their special

features; or as if a special ether

determined the specific gravity of

everything found in it.'

This he writes in his 'Introduction

to a contribution to a critique

of political economy'. But with

probably deeming himself, and the

adherents of his

historic-materialistic theory, the

impersonation of that ether, is,

with the atheistic cry of nonsense,

which classically after Epicurus

factually was pronounced over the

(dis-)believer and not so much over

God and His gods, nevertheless at

the onset of the twenty-first

century shamelessly worldwide the

materialistic doctrine put in

practice of the, now also

socialistically excercised, sex and

money belief, with the worship of

the idols called Mammon and Viagra.

In that disbelief then furthermore

everyone is written off who dares to

voice a not-to-realize ideal,

contrary to the misanthropic, but

factually perverse,

relativistic/cynical paradigm. Karl Marx

(1818-1883), postmodern man knows

but one belief and one

mantra: 'that's nonsense!'. In a

depression being disappointed about

the enduring abuse by the human

being,

Religion is

nothing but hypocritical nonsense.

But was it not

the ancient philosopher Epicurus who

(341-270 b. Chr.) in his 'Letter

to Menoeceus' already said

that 'Not the man who denies the

gods that are worshiped by the

masses, but the one who ascribes

to the gods what the mass believes

about them, is godless'? Marx

is not entirely without a form of

belief or a God. He also builds on a

connecting element: 'There is, in

every social formation, a branch

of production which determines the

position and importance of all

others; and the relations

obtaining in this branch

accordingly determine the

relations of all other branches,

as well. It is as though light of

a particular hue were cast upon

everything, tinging all other

colors and modifying their special

features; or as if a special ether

determined the specific gravity of

everything found in it.'

This he writes in his 'Introduction

to a contribution to a critique

of political economy'. But with

probably deeming himself, and the

adherents of his

historic-materialistic theory, the

impersonation of that ether, is,

with the atheistic cry of nonsense,

which classically after Epicurus

factually was pronounced over the

(dis-)believer and not so much over

God and His gods, nevertheless at

the onset of the twenty-first

century shamelessly worldwide the

materialistic doctrine put in

practice of the, now also

socialistically excercised, sex and

money belief, with the worship of

the idols called Mammon and Viagra.

In that disbelief then furthermore

everyone is written off who dares to

voice a not-to-realize ideal,

contrary to the misanthropic, but

factually perverse,

relativistic/cynical paradigm.

The

postmodern philosopher Jacques

Derrida

(1930-2004) spoke of deconstruction

when it is about the appreciation of

interpretation sensitive human forms

of existence, or 'texts', as he

calls it: each may see in them

whatever he likes, and so it would

be impossible to arrive at a

complete and coherent concept and

ditto society. He is correct in

saying that books alone do not

suffice and that, mutually

exercising respect, texts never

deliver one an all-embracing or

coherent image of reality. And it is

also certain that, in a depression,

without having a clear picture in

one's mind, there indeed may be

spoken of a literal deconstruction

of the image of time of the

observer. Man depressed is disturbed

to the triple nature of time: the

past is black, the future is

invisible and the present is

unpleasant. As a cultural institute

he breeds a no-future generation of

people suffering under what

psychologists like Martin

Seligman call

'learned helplessness', a mental

affliction of the self-doubting

kind, in which no solace is found of

an absolute reference we could

address with the name of God, and by

which we could pull ourselves out of

our pool of misery. We saw that also

relativism, as a

faulty combination of scientific

power and philosopical knowledge,

traditionally decried by the Pope

and exposed as a compensation, came

to a fall with the refutation of

Einstein building on a non-existent

limit of light speed, the man who

appeared to be the God and Prophet

of it, but who, according to the

different empirical results of

scientific experiments about the

speed of light at the onset of this

century, turned out not to be

irrefutable in it.

Even though

it is indeed difficult to prove

materially, because of

paradigmatically being bound, it

must be said that the ether simply

exists, once we know why we in that

context have to speak of the

forcefield of the Milky Way existing

as a fixed frame of reference. Time

did not turn out to be absolute in

the velocity of changing with the

light, but time was absolute in the

quality of the changing itself. As Herakleitos (535-447

B.C.) said: everything is in flux, panta

rhei. The relativistic

depression, which after Nietzsche

was rampant in the political era to

the inability to supersede Marx'

atheistic, social idealism, is thus

unmasked as a form of attachment in

defiance of that change, contrary to

the absolute authority of our

dynamical Father of Time and His

sacred ether, the factual godhead of

the classics who by Nietzsche was

declared to be as dead as the mean,

mechanical time of the, from this

view seen, hopelessly outdated

clock. Even a schoolboy these days is capable

of lecturing the physicists of the

fallen and, all too linear

conceived, standard time paradigm.

So succeeded the talented young man

Peter

Lynds (born

1975) in 2003 by, (even before

Consoli's interpretation of

Düsseldorf already), stating that

there are no separate moments of

time therein,

and that only a continuous

change exists which one could

consider absolute. Furthermore the

cynicism, the canine variety of the

biting sarcasm, never turned out

to be a successful rule of state,

apart from the isolationism and the

paranoia of autarkies like Hitler's Germany

and the Cambodja of Pol Pot, but

rather constitutes a mental

aberration of possibly

sociopathically abreacting, like a

cactus as thorny, depressed people

mainly of interest for practicing

psychologists and psychiatrists.  Being

intellectually perverted in the

negativism of a mutually confirmed

cultural pessimism, one, like a cult

leader e.g., loves to

keep up, and also be dutiful with,

the appearance of authority,

progress and civilization. But one

went, disturbed being postmodern, in

fact personally, intellectually and

socially bankrupt, uncertain about

one's identity therewith

philosophically being lost, like we

noted with the

declaration of order already.

That is the conclusion we from now

have to work with in this last part

of the filognosy

of our comprehension. It is, nearing

the end of our argument, perfectly

clear by now that, without a sober

methodical approach, a proper

knowledge of facts, an effective and

art loving analysis, a fine

disciplined sense for spiritual

unification according to the

principle, and a well organized

respect for the classical, meekly

and brotherly coexisting, and each

other succeeding, spiritual schools

of learning, there can be no mention

of a meaningful political approach

of respect for, and from, the

civilized person in all his

historical, social and scientific

glory. It is evident that, with but

a color sensitive ego desire, with

but an economic/judicial argument,

with but a conservative attitude of

private considerations of decency

and virtue, and with but a single

socialist ideal of sharing honestly,

in a humanistic understanding for

the weaknesses, we will not be able

to cope politically. None of the

dictatorships derived from a

narrowed politicized consciousness

will last, because of the inequity

they represent with their one-sided

dictates. The Tocqueville says

thereto: 'The consequence of this

has been that the democratic

revolution has been effected only

in the material parts of society,

without that concomitant change in

laws, ideas, customs, and manners

which was necessary to render such

a revolution beneficial.' If

democracy really wants to be a

blessing, we will have

to acknowledge that, for the sake of

her quality, a certain change of

mind, a change in the consciousness

of the people, is required. And so

we thus arrived at the filognosy

which, understood from the causality

of the person or the factual

substance of our investigation, more

or less as a precondition demands

the scientific sobriety and

principled spirituality, or else

presents these as the indispensable

elements needed to enjoy the fruit

of a beneficial political

disposition of emancipated people

taking responsibility. Being

intellectually perverted in the

negativism of a mutually confirmed

cultural pessimism, one, like a cult

leader e.g., loves to

keep up, and also be dutiful with,

the appearance of authority,

progress and civilization. But one

went, disturbed being postmodern, in

fact personally, intellectually and

socially bankrupt, uncertain about

one's identity therewith

philosophically being lost, like we

noted with the

declaration of order already.

That is the conclusion we from now

have to work with in this last part

of the filognosy

of our comprehension. It is, nearing

the end of our argument, perfectly

clear by now that, without a sober

methodical approach, a proper

knowledge of facts, an effective and

art loving analysis, a fine

disciplined sense for spiritual

unification according to the

principle, and a well organized

respect for the classical, meekly

and brotherly coexisting, and each

other succeeding, spiritual schools

of learning, there can be no mention

of a meaningful political approach

of respect for, and from, the

civilized person in all his

historical, social and scientific

glory. It is evident that, with but

a color sensitive ego desire, with

but an economic/judicial argument,

with but a conservative attitude of

private considerations of decency

and virtue, and with but a single

socialist ideal of sharing honestly,

in a humanistic understanding for

the weaknesses, we will not be able

to cope politically. None of the

dictatorships derived from a

narrowed politicized consciousness

will last, because of the inequity

they represent with their one-sided

dictates. The Tocqueville says

thereto: 'The consequence of this

has been that the democratic

revolution has been effected only

in the material parts of society,

without that concomitant change in

laws, ideas, customs, and manners

which was necessary to render such

a revolution beneficial.' If

democracy really wants to be a

blessing, we will have

to acknowledge that, for the sake of

her quality, a certain change of

mind, a change in the consciousness

of the people, is required. And so

we thus arrived at the filognosy

which, understood from the causality

of the person or the factual

substance of our investigation, more

or less as a precondition demands

the scientific sobriety and

principled spirituality, or else

presents these as the indispensable

elements needed to enjoy the fruit

of a beneficial political

disposition of emancipated people

taking responsibility.

With religion

as the study we never graduate from,

and politics as the right-minded

practice to it which time and again

has to recapitulate and adapt, confer

and revise, we have arrived

at the necessity of a reliable,

thorough vision for the future.

Without a clearly outlined ideal,

without a purpose in mind, as said,

postmodern mankind is not capable of

emerging, from it's narcomaniac,

anxiety-neurotic, obsessive depression

and cynicism, as being cured and thus

being capable of finding a

rational/democratic equilibrium

between the charitable enlightened

humanistic, and the materially

motivated, traditional

moralistic/pragmatic  argument.

What should we do when we, whether

depressed with Nietzsche or not, have

to accept our responsibility, not

being able any longer to play hide and

seek behind the back of the

traditional authorities of in fact the

parson and the reverend? Who can tell

us, grown-ups of intellectual

independence, what we would have

learned and would have to engage in

next? Would that be science, so

divided in itself? That is, despite of

the behavioral side of science and

theology, not personal enough. With

the answer found in the commentaries

of oppositional, dialectical and

democratic politics, and therewith

theologically following in the

footsteps of Desiderius

Erasmus (1466 or

1469-1536) who stated that: 'It is

wrong like children to hold on to

the letter and not mature to the

freedom of the spirit',

we see the greek word of polis

emerging as the etymological root of

the concept of politics, meaning a

city or community determined by a

certain exercise of authority or form

of administration. It is evident that

we, from the scientific via the

spiritual and the religiosity of

personal confessions and conversions,

having arrived at the political

perspective, the 'talent to rule' the

polis, we inevitably have to

ponder over the authority and the

powers that be in holding together our

society(-ies) on this planet. argument.

What should we do when we, whether

depressed with Nietzsche or not, have

to accept our responsibility, not

being able any longer to play hide and

seek behind the back of the

traditional authorities of in fact the

parson and the reverend? Who can tell

us, grown-ups of intellectual

independence, what we would have

learned and would have to engage in

next? Would that be science, so

divided in itself? That is, despite of

the behavioral side of science and

theology, not personal enough. With

the answer found in the commentaries

of oppositional, dialectical and

democratic politics, and therewith

theologically following in the

footsteps of Desiderius

Erasmus (1466 or

1469-1536) who stated that: 'It is

wrong like children to hold on to

the letter and not mature to the

freedom of the spirit',

we see the greek word of polis

emerging as the etymological root of

the concept of politics, meaning a

city or community determined by a

certain exercise of authority or form

of administration. It is evident that

we, from the scientific via the

spiritual and the religiosity of

personal confessions and conversions,

having arrived at the political

perspective, the 'talent to rule' the

polis, we inevitably have to

ponder over the authority and the

powers that be in holding together our

society(-ies) on this planet.

Man

wrestling with the moral authority

and the exercise of power is, with

the duty assume of adulthood, rather

eager to God's position. But

we are in trouble assuming that

power, with problems one inevitably

has to face in politics. In the

cinema there was of the director Tom

Shadyac, 2003, a nice story about it

called 'Bruce Almighty'. It

describes how a frustrated reporter,

who sees everything working against

him in life, thereupon challenges

God to prove that not He Himself is

the lazy, unemployed ass not doing

his duty. God then proves Himself by

handing His powers over to him, but

not without the message that he has

to abide by two rules: he cannot say

he is God, and he must respect the

free will of the people. And thus

being engaged, our hero,

hilariously drawn by Jim Carrey,

ends up finally turning in his

absolute power, realizing that the

love for the goodness of reality as

it is, is ruling the world, and not

so much the special abilities with

which one cannot subdue the free,

human will anyway. The combination

of the concepts of freedom and

authority constitutes a

philosophical problem.  In his book

Leviathan the

philosopher Thomas

Hobbes

(1588-1679), in 1651, clarifies

that to accept a certain form of

authority, whether of God or not, is

something inevitable if we do not

want to end up in a chaos of

'everyone against everyone'. So

stated, next to that, on a later

date the australian archeologist V. G.

Childe,

(1892-1957), in following after the

about the - in the personal and

collective history alternating -

thought systems dialectically reasoning

philosopher G. W. F.

Hegel

(1770-1831), that each rule of

state, implies a dominance of

hierarchy, a pecking order, a

stratification in societal classes,

which he observed as emerging from

the free, gathering and hunting man

of nature who managed to organize

himself in a 'revolutionary' way

from being agricultural into having

cities and thus arriving at a

division of labor. As seen from his

marxist vision, therein an

evolution of the forms of state took

place, in a 'struggle about the

means', means like stone, bronze and

iron, with the thereto belonging

eras, which still generally accepted

carry those names. From T. Kuhn

(1922-1996) we now know that that

'struggle' must be considered

paradigmatical, and not directly

social. It is more the stir in the

upper regions than in the lower ones

what is going on, even though

matters misapprehended, may

sometimes work maliciously out in a

downward direction. Plato, as early

as in the

Republic, already

from his side spoke, more refined as

Hobbes, of a hierarchy of rules of

state offering the perspective of an

aristocracy of nobles, which by a

timocracy directed at (military)

honor and a 'happy-few'-oligarchy of

higher officials, slides down in the

direction of a tardy bureaucratic

democracy, of politically

belligerent representatives, of a

doubtful heritage, which,, desperate

in a general call for authority,

eventually corrupts into a

dictatorship of 'I am God'. Also the

Vedic option offers the vision of

such a state of affairs with the

sliding down of the noble rule in

the chaotic chronic quarrel of kali-yuga,

even though they see it as something

cyclic in ages, covering many

thousands of eras. The sociologist Max Weber

(1864-1920) used a division in

three, in discussing the legal

authorities, and this division can

be recognized as a further insight

into this process of historically

sliding down, or eroding, into the

immoral chaotic and impersonal

uncertainty of authority. In his book

Leviathan the

philosopher Thomas

Hobbes

(1588-1679), in 1651, clarifies

that to accept a certain form of

authority, whether of God or not, is

something inevitable if we do not

want to end up in a chaos of

'everyone against everyone'. So

stated, next to that, on a later

date the australian archeologist V. G.

Childe,

(1892-1957), in following after the

about the - in the personal and

collective history alternating -

thought systems dialectically reasoning

philosopher G. W. F.

Hegel

(1770-1831), that each rule of

state, implies a dominance of

hierarchy, a pecking order, a

stratification in societal classes,

which he observed as emerging from

the free, gathering and hunting man

of nature who managed to organize

himself in a 'revolutionary' way

from being agricultural into having

cities and thus arriving at a

division of labor. As seen from his

marxist vision, therein an

evolution of the forms of state took

place, in a 'struggle about the

means', means like stone, bronze and

iron, with the thereto belonging

eras, which still generally accepted

carry those names. From T. Kuhn

(1922-1996) we now know that that

'struggle' must be considered

paradigmatical, and not directly

social. It is more the stir in the

upper regions than in the lower ones

what is going on, even though

matters misapprehended, may

sometimes work maliciously out in a

downward direction. Plato, as early

as in the

Republic, already

from his side spoke, more refined as

Hobbes, of a hierarchy of rules of

state offering the perspective of an

aristocracy of nobles, which by a

timocracy directed at (military)

honor and a 'happy-few'-oligarchy of

higher officials, slides down in the

direction of a tardy bureaucratic

democracy, of politically

belligerent representatives, of a

doubtful heritage, which,, desperate

in a general call for authority,

eventually corrupts into a

dictatorship of 'I am God'. Also the

Vedic option offers the vision of

such a state of affairs with the

sliding down of the noble rule in

the chaotic chronic quarrel of kali-yuga,

even though they see it as something

cyclic in ages, covering many

thousands of eras. The sociologist Max Weber

(1864-1920) used a division in

three, in discussing the legal

authorities, and this division can

be recognized as a further insight

into this process of historically

sliding down, or eroding, into the

immoral chaotic and impersonal

uncertainty of authority.

Departing

from the traditional authority

of the Church and the nobles, with

respect for the person of God,

according Weber the charismatic

authority of dictators evolved. like

that

of Hitler, Napoleon, Stalin and Mao

in defiance of the holiness, which,

once turned over, results in the

authority of the legal-rational

authority of an

institutionalized government, of

which the power of rule controls

itself, rather than the individual

person at it's service. And thus we,

with the historical sense for the

order of time, sociologically arrive

from personalism at formalism, the

reality of a culture of settled

state officials, which so nicely was

decried in e.g. the book and the

motion-picture 'A

Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy' of

Douglas Adams 1979/2005. Fallen in

ignorance about the impurely lived

(religious) remedies and being fixed

on the problematic only, we are

again ripe for the psychologist,

just to notice that we, this way,

still, with all kinds of

schizoidisms, are entangled in a

certain ego-determined form of being

split within. Fro the angle of

social psychology one may discern

five forms of exercising power in

this: the power of rewarding,

the power of punishing, the

power to delegate, the power

of merit and the power of expertise.

The postmodern dissension and

fallenness is then characterized by

the eroded state, which, by delegation

to local authorities, rewards

the ones adapted and punishes

the transgressors, while, it

being impersonal, in its

administration is faced with a

popular compensation of charismatic

celebrities of a doubtful breed, who

only then are really a

threat to the establishment of the

legal order, when they have acquired

a certain expertise in

relating to the popular vote upon

which, democratically, the state

itself thus also is building. With

all scientific analysis of the

problem we thus have not yet gotten

out of the postmodern depression of

the modern intellect. We may, being

of denial about the depression or

not, see the matter as inevitably

inherent to the spoilt nature of

the, by Niccolņ

Machiavelli

(1469-1527) already described, man

of a dubious moral fiber lusting for

power, without realizing that the

ideal of an utopian state was never

lost, despite the reprehensible

formulations of utopists like Aldous Huxley

(1894-1963) ('promiscuity is your

duty' in Brave

New World) and B. F. Skinner

(1904-1990) ('no individual

parenting' in Walden Two),

who were not as effective in

reasoning out the matter as did the

original and canonized utopist Thomas More

(1478-1535) in his Utopia

('Neverland') of 1516.  The ideal

of a god-conscious world without

tyranny, superfluous wealth, land

owners, however difficult to attain,

cannot really perish, because it

serves a basic psychological need

and thus, like we saw with

discussing the self-ideal in section

III-a, it constitutes a reality

integrally part of our existence,

which, also postmodern, surfaces in

S.F. t.v.-series like Startrek e.g. Man

without his dreams is as good as

dead. However unrealistic the utopia

of the God Mythra of More may seem

to be, still it constitutes, with

the Vedic god of time Kāla, and the

thereto belonging avatāras

of Vyāsa, the indispensable aim and

cultural root where all political

movements with their programs, more

or less consciously, depart from and

strive for. Each has, as taken from

the passion, or else from the

goodness, in politics an ideal of

order and authority in mind on the

one hand, and an ideal of freedom

and happiness on the other hand,

which is not strange to the person

but rather of justice to him. But

with the relativistic splitting up

of time and place in modern time, as

done by the standard time politics

of using pragmatic/economic

arguments, no justice done is

to the person in his control with

the ether and in his natural

functioning with brain halves,

'hemispheres', that, on the

contrary, are fully occupied with

linking space to time. The, with all

goodwill therewith conflicting,

indeed wishing to doing justice to

When, motivated for the good, one in

opposition therewith wants to do

justice to that natural order of the

person, that does not imply that one

immediately agrees about what that

order exactly would be and in which

way it should be respected, about

how those two elements of freedom

and bondage would have to be

combined in a coherent policy

acceptable to both (natural) science

and spiritualilty (the reality

according to its principles). Even

though Jesus said that for God the

Father things on earth had to happen

as they are in heaven, still is one

not immediately of acceptance for,

or familiar with, the verse of Vyāsa

in which the respect for

specifically the place and the time

is combined with the respect for the

person (S.B. 4.8:

54): 'Om namo bhagavate

vāsudevāya [my respects for

Vāsudeva, the Supreme Lord]; with

this mantra [called the dvādas'āksara-mantra]

the learned one should exercise

respect for the physical nature of

the Lord, the way it should be done,

with the diverse paraphernalia, and

as someone conversant with the

differences to place and time [des'a-kāla-vibhāgavit].' The ideal

of a god-conscious world without

tyranny, superfluous wealth, land

owners, however difficult to attain,

cannot really perish, because it

serves a basic psychological need

and thus, like we saw with

discussing the self-ideal in section

III-a, it constitutes a reality

integrally part of our existence,

which, also postmodern, surfaces in

S.F. t.v.-series like Startrek e.g. Man

without his dreams is as good as

dead. However unrealistic the utopia

of the God Mythra of More may seem

to be, still it constitutes, with

the Vedic god of time Kāla, and the

thereto belonging avatāras

of Vyāsa, the indispensable aim and

cultural root where all political

movements with their programs, more

or less consciously, depart from and

strive for. Each has, as taken from

the passion, or else from the

goodness, in politics an ideal of

order and authority in mind on the

one hand, and an ideal of freedom

and happiness on the other hand,

which is not strange to the person

but rather of justice to him. But

with the relativistic splitting up

of time and place in modern time, as

done by the standard time politics

of using pragmatic/economic

arguments, no justice done is

to the person in his control with

the ether and in his natural

functioning with brain halves,

'hemispheres', that, on the

contrary, are fully occupied with

linking space to time. The, with all

goodwill therewith conflicting,

indeed wishing to doing justice to

When, motivated for the good, one in

opposition therewith wants to do

justice to that natural order of the

person, that does not imply that one

immediately agrees about what that

order exactly would be and in which

way it should be respected, about

how those two elements of freedom

and bondage would have to be

combined in a coherent policy

acceptable to both (natural) science

and spiritualilty (the reality

according to its principles). Even

though Jesus said that for God the

Father things on earth had to happen

as they are in heaven, still is one

not immediately of acceptance for,

or familiar with, the verse of Vyāsa

in which the respect for

specifically the place and the time

is combined with the respect for the

person (S.B. 4.8:

54): 'Om namo bhagavate

vāsudevāya [my respects for

Vāsudeva, the Supreme Lord]; with

this mantra [called the dvādas'āksara-mantra]

the learned one should exercise

respect for the physical nature of

the Lord, the way it should be done,

with the diverse paraphernalia, and

as someone conversant with the

differences to place and time [des'a-kāla-vibhāgavit].'

As we saw

with the discussion about the

fields of action in section

I-B, there is, to begin with, no

immediate agreement about how the

political field should be described.

The left-right spectrum is described

by e.g. the Eysenk model, the

Nolan-distribution, the Political

Compass, de Pournelle-chart, the

Inglehart-values and the Frisian

Institute (see Wikipedia: Political

Spectrum); they are

rather structuralistic. All these

models have in common that they fail

in a certain philosophical lead of

unequivocality and clarity. That

clarity though does exist ever since

Aristotle, who in About the

cosmos stated: '... that

this is the most admirable of

political solidarity: namely that

she from the diversity brings

about a oneness and from

inequality an equality, capable of

withstanding each natural or

coincidental occurrence. .....In

matters great like these nature teaches us

that equality is the guardian of

solidarity and that solidarity is

the guardian of the cosmos, which

is the progenitor of each and all

and of beauty to the highest

degree.' As early as in A

Small Philosophy of Association we

concluded accordingly, that we

axiomatically - Vedically thus and

not just european with theoreticians

of democracy like Aristotle en

Alexis de Tocqeville - deriving from

the dictum 'unity in diversity',

were dealing with a quantitative ąnd

qualitative dimension, on the basis

of which we have the two dualities

of the quantitative - individual as

opposed to the social, and the

qualitative - concrete of matter as

opposed to the abstract of having

ideals, as if it concerned two

intertwined yin-yang-symbols (see

the fields-table). Also incorporating

the Chinese philosophy of the

balance in nature of Lao Tzu (6th

century B.C.) and the balance in the

reflection thereof in the culture of

rule of Confucius (551 - 479

v. Chr.), as also the japanese

Shinto philosopher Kanetomo

(1435-1511), who said that

equilibrium is divinity, with this

original clarity now,

filognostically correct of

reference, and thus being certain of

our matter, the confusion of the

thought models concerning the

political order and the exercise of

authority of the modern state must

come to a close. It may be clear

that, reasoning from the Vedic root,

with the false ego - the

identification of oneself with the

material self-interest - a political

struggle has ensued of

interestgroups that no longer are

fully in touch with their

status orientation, nor

integer with the fields of action,

the way it, more or less, with ease

can be recognized in the

rational/legal authority of state

departments. The political, the

official and the lawful powers

happen to be different options of

rule - like Charles

Montesquieu

(1689-1755) recognized it in his trias

politica of the legislative,

executive and judicial powers 0f

state -, even though all three of

them receive an income from the same

state. We simply have officials of

discussion, who with laws engaged

have to play their roles in the

chambers of discussion, and there

are officials of order, who simply

for a state department execute the

matters of state, whatever their

personal, political preference, ąnd

we have judges, who have to guard

the human rights in this, to

preclude a dictatorship of officials

or civil initiatives. The ideal

consists of a healthy common sense

in relating to this (political)

reality, and the problem in going

for it consists of the illusions

(the māyā and moha)

of people caught

in the notions of the false ego (ahankāra),

in

-isms, in which one is not

able to find the balance between the

end of a vision served and the means

of the opulence fundamental to it.

between the vision cherished and the

quality or opulence aimed, at cannot

find the balance or the proper

entry. That is what appears to be

the only clear logical/filognostical

answer to the matter. And if we face

reality as being the holy purpose,

the holy grail of democracy, in such

a scientific way that there is also

understanding for all the escapades

of the modernist ego, we neither

have to be afraid of what the

psychologist/philosopher Karl Popper

(1902-1994) warned against with his

plea for the 'open society' of a

liberal democracy. Also incorporating

the Chinese philosophy of the

balance in nature of Lao Tzu (6th

century B.C.) and the balance in the

reflection thereof in the culture of

rule of Confucius (551 - 479

v. Chr.), as also the japanese

Shinto philosopher Kanetomo

(1435-1511), who said that

equilibrium is divinity, with this

original clarity now,

filognostically correct of

reference, and thus being certain of

our matter, the confusion of the

thought models concerning the

political order and the exercise of

authority of the modern state must

come to a close. It may be clear

that, reasoning from the Vedic root,

with the false ego - the

identification of oneself with the

material self-interest - a political

struggle has ensued of

interestgroups that no longer are

fully in touch with their

status orientation, nor

integer with the fields of action,

the way it, more or less, with ease

can be recognized in the

rational/legal authority of state

departments. The political, the

official and the lawful powers

happen to be different options of

rule - like Charles

Montesquieu

(1689-1755) recognized it in his trias

politica of the legislative,

executive and judicial powers 0f

state -, even though all three of

them receive an income from the same

state. We simply have officials of

discussion, who with laws engaged

have to play their roles in the

chambers of discussion, and there

are officials of order, who simply

for a state department execute the

matters of state, whatever their

personal, political preference, ąnd

we have judges, who have to guard

the human rights in this, to

preclude a dictatorship of officials

or civil initiatives. The ideal

consists of a healthy common sense

in relating to this (political)

reality, and the problem in going

for it consists of the illusions

(the māyā and moha)

of people caught

in the notions of the false ego (ahankāra),

in

-isms, in which one is not

able to find the balance between the

end of a vision served and the means

of the opulence fundamental to it.

between the vision cherished and the

quality or opulence aimed, at cannot

find the balance or the proper

entry. That is what appears to be

the only clear logical/filognostical

answer to the matter. And if we face

reality as being the holy purpose,

the holy grail of democracy, in such

a scientific way that there is also

understanding for all the escapades

of the modernist ego, we neither

have to be afraid of what the

psychologist/philosopher Karl Popper

(1902-1994) warned against with his

plea for the 'open society' of a

liberal democracy.

He stated that the

reality of evolving forms of state

as being a lawful one, like e.g. is

envisioned by the evolutionary model

of Marx and Hegel, does not imply

that one thus can design oneself a

future. According to Popper the

utopia is potentially a dangerous

and totalitarian vision of reality,

for it implies that repeatedly the

freedom of the individual must be

sacrificed for the sake of the

higher purpose, because if one

leaves man the choice in his lusty

nature, nothing will come of the

envisioned state. From the Vedic

axiom seen that must be

confirmed. It is not so much about

creating another world and pushing

oneself off against the rule of a

doubtful form of freedom by means of

overturning the regime with a

violent revolution. What is of

interest is to cast off

individually, and thereafter also

subculturally or even collectively,

in the end the shackles of the

illusions upheld from the profit

mind, and face the original reality,

thus finding the happiness, even

though that would not directly be

the happiness of each, and

ultimately indeed possibly might be

another time or world. One cannot

better the world turning oneself

away from it, neither socialist nor

individualist, or push oneself off

against it; one has to see it as it

is, and then, with bettering one's

own life, also as an example and

support for others being of service

with it, be happier with that, in

the sense of finding a life better

in agreement with one's own nature.

And so it is, not just as

Vyāsa put it with his concepts of svadharma

and svarūpa (one's own nature

and form), but is it also like

the philosopher Seneca in his

selfrealization stated it in 'A

Happy Life' III.3, later on in

history talking about that better

life. Like Popper indicated it with

his idea of the 'piecemeal

engineering' of a gradual

realization of politically set

targets, also with Vyāsa already

that idea is found in his per paramparā,

or disciplic succession, handing

down of spiritual authority, which

thus allows for but a step by step

(B.G. 6: 25) cultural

evolution, in which the individual

first of all is faced with a

'bitter' hangover from the lesson

learnt, and only later on may

harvest the 'sweet' of a better

practice (B.G. 18: 36-38) - a

practice of a filognostical,

personally conveyed, virtuous way

and proper life habit of gratitude

and servitude, equal to the moksha

of individual liberation or else the

individual/subcultural attaining on

this planet of vaikunthha,

the Vedic heaven of that order of

life, in which there is no (vai-)

dullness and sloth (-kunthha)

any more, and one therefore has

nothing to fear.

The fake democracy must,

as we before saw in the Small

Philosophy of Association, be

remedied with a self-certain sense

of order, with a certain settled,

representative democracy in which

the concept of freedom is no longer

bound to chaos as it is to order; as

it was also confirmed e.g. in 2003

by the muslim-writer and journalist

Fareed

Zakaria in his